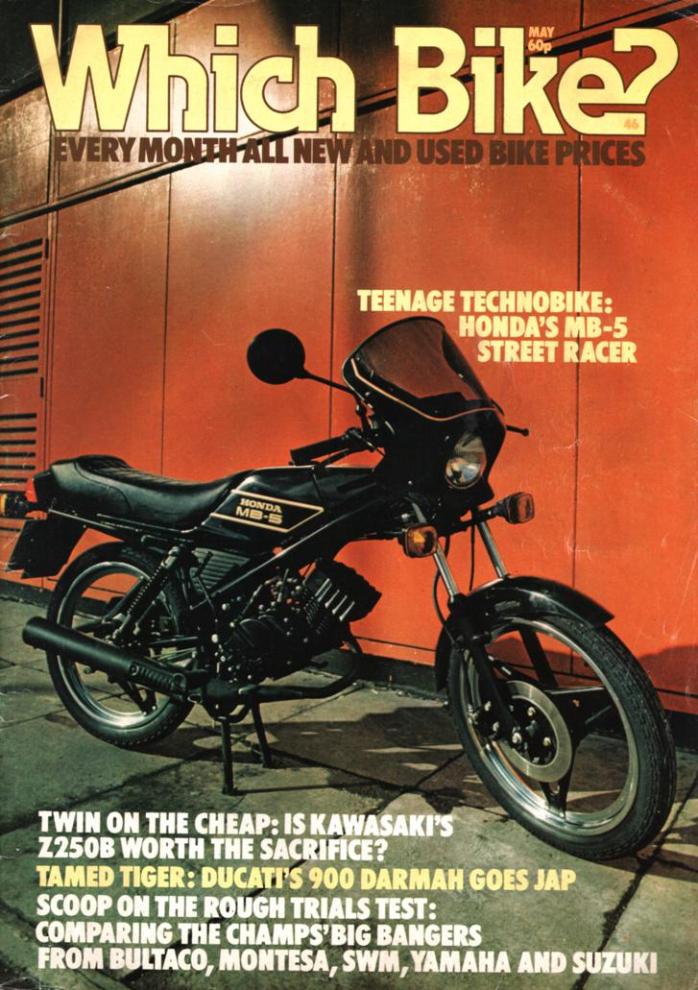

Which Bike? Road Test from May 1980

Should you imagine, if you happen to be peering down from a superbike or car, that those little sixteeners buzzing through the traffic are motorcycling’s evolutionary equivalent of the primeval ooze, then think again. The missing link has arrived.

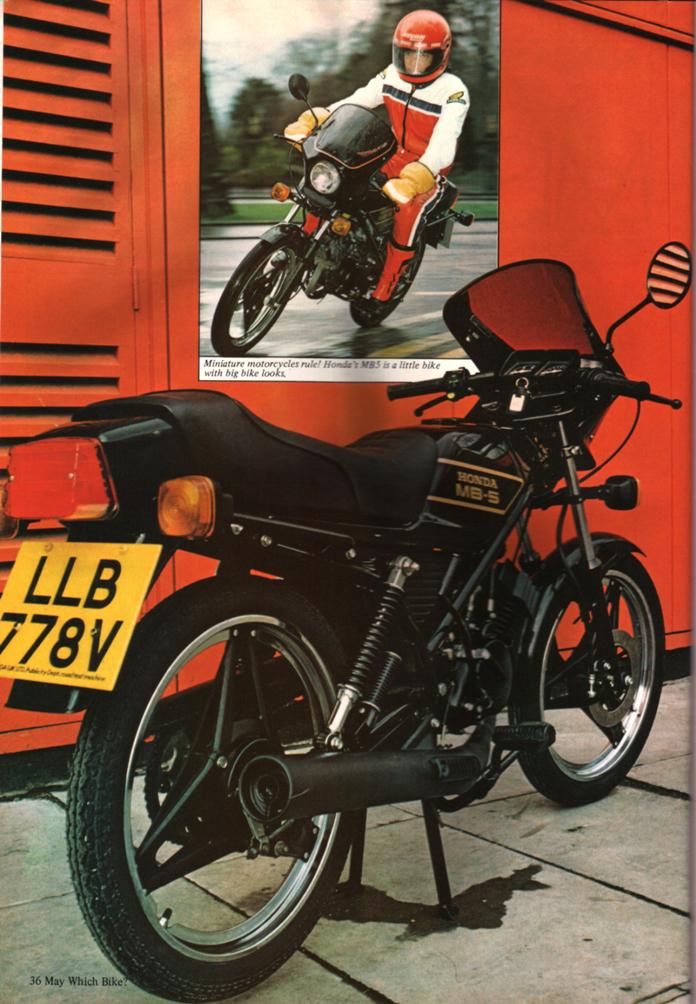

Honda’s new MB5, and it’s trail style MT5 stablemate, is as radically different in the world of restricted 50cc machines as the six cylinder CBX was to the performance bike class.

True, it can still only just manage the mandatory top speed of around 35mph. In fact the MB5 can be beaten off the mark by some single or two speed mopeds. But that is of little consequence. For in the case of the Honda looks are all. And if looks are the criterion, then the MB5 is a high performance bike.

In many other European countries, the MB5 really is a high performance too, it’s two stroke engine being tuned to develop 7 bhp and push the top speed to over 60 mph. For Britain however, a number of design details cut the power to 2.5 bhp. The rider isn’t short changed else where though and gets the full complement of striking styling feature found on the 60mph job.

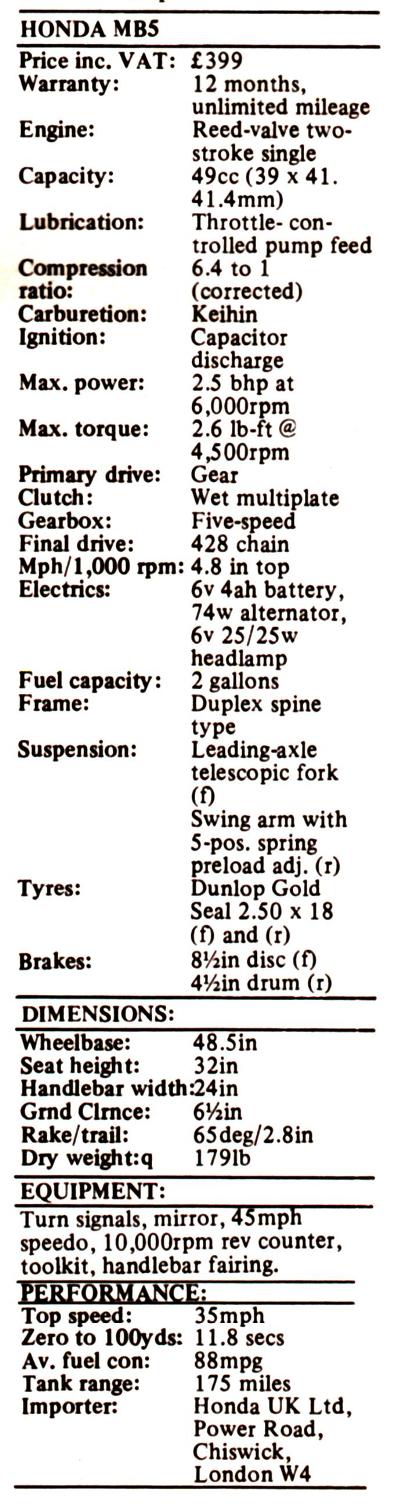

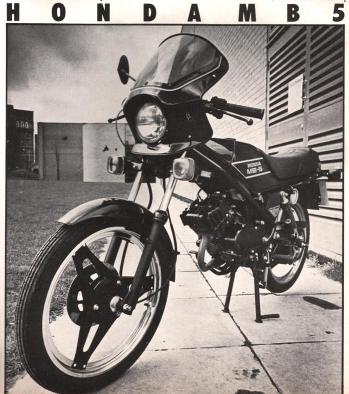

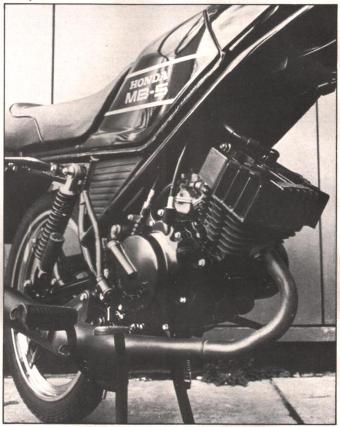

The most predominant feature is the frame, and this sets the scene for the rest of the bike. It’s a simple triangulated tubular structure with two tubes running from the steering head to the swing arm pivot and is braced by a pressed steel centre spine. The engine hangs from the frame and connects to the gusseting around the swing arm.

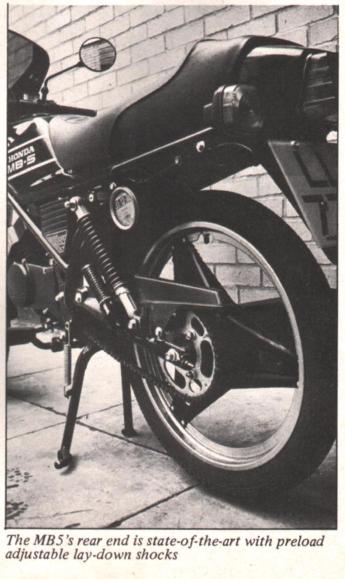

The suspension is no less up to date with a leading axle front fork delivering nearly five inches of movement. The rear suspension is controlled by a pair of laid down shocks with spring pre-load adjustment. Unusually for a sixteener both ends of the bike have damping, and very effective damping too. For such a light (179lbs dry) bike the combination of plenty of well controlled travel is a revelation and it shows up with superlative handling.

Naturally, with a chassis capable of taking nearly three times as much power, the MB5 is hardly overloaded and this means the bike is utterly safe at it’s performance limits. It can be flung around confidently thanks to the positive steering and the low riding position. Only time the rear end was stretched was when a passenger was carried. Even then the springs only bottomed occasionally and this was because of the curious geometry that effectively lowers the spring rate as they are compressed.

Tyres are Japanese made Dunlop Gold Seal’s in full 2.50 x 18 sizes. To cater for the higher loading the rear has a six-ply rating. Both covers provided excellent road holding.

The tyres are mounted on yet another type of Honda Comstar wheel. Since the bike is relatively light, these have just three pairs of pressed alloy spokes riveted to chromed steel rims and bolted to hubs.

If the bike is diminutive and toy like in appearance it certainly doesn’t feel that way. The handgrips are clip-on type in a one piece construction that doubles as the top yoke for the fork. The fuel tank, seat and footrests give a substantial appearance from the riders perch. The seat is more than long enough to take a passenger and has a solid grab rail along each side but the passenger foot rests mounted on the swing arm, are too high for real comfort.

The hand controls are easily as good as those found on the bigger Honda’s. The levers are dog-leg style so that smaller hands can grip them comfortably and the switch-gear consoles, finished in matt black like the rest of the “dashboard” are smartly designed with an effective appearance. New is the turn signal switch which is angled to the left so that your thumb can get at it quicker.

Braking gear is equally up to scratch. Up front there’s an 8½” inch hydraulically operated disc with the floating calliper mounted behind the fork leg in the current vogue. The master cylinder has a miniature rectangular reservoir on the handlebar lever. Since it’s made for a 60mph machine, there’s more than enough power and feel when you’re stopping from half that speed. On the rear wheel there’s a rod operated drum brake.

As on the new CB250RS four-stroke single, the instrument faces are rectangular with turn signal repeater and neutral lamps.

Electrically the MB5 is much more lavishly equipped than any other 50cc sixteener machines. The engine has a 74-watt generator with two sets of coils, one of which supplies the 25-watt headlight directly, the other charging the six-volt, four-amp-hour battery through a simple silicon rectifier. The battery powers the turn signals , rear brake light and instrument lamps, ensuring they don’t go dim with low engine revs.

You might expect that within the limitations of the sixteener regulations, there isn’t much that can be done with the manufactures to put more zip into their bikes.

That’s true of the maximum power output, which generally dictates the top speed of the machine. What is also vitally important as well is the spread of power. If for example, your 50cc engine delivers a high output with a very narrow power band then the gearing will have to be perfect otherwise the bike will suffer on gradients, up and down.

Honda’s little two-stroke engine is sophisticated in the extreme in this respect. And although it only develops a modest 2.5bhp at 6000rpm there’s still plenty on tap at 7500rpm and will pull heartily from as low as 3000rpm . Some measure of the engines flexibility is that the torque peaks at 4500rpm.

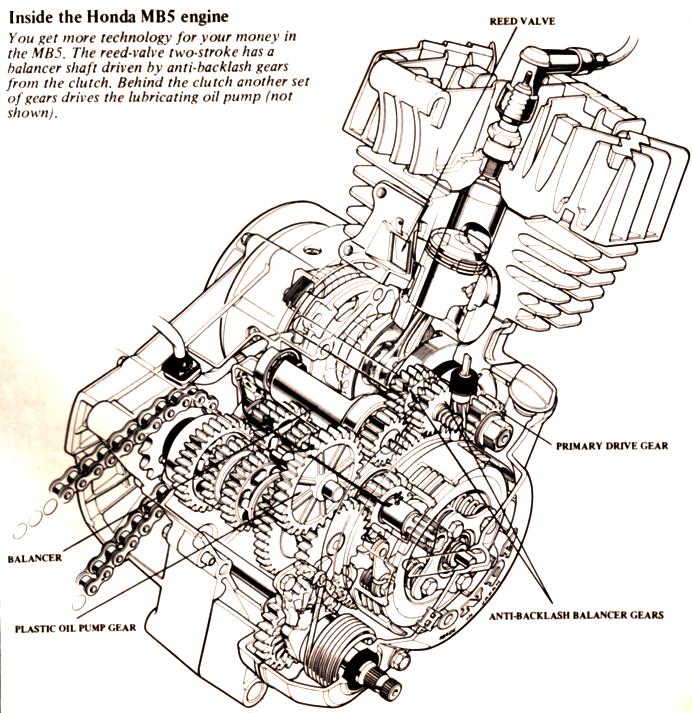

Honda have gone to a great trouble to ensure that the motor can’t be easily restored to its unrestricted form. The porting is tuned for the lower output and small Keihin carburettor and reed valve casing have very limited openings. And while the whole construction of the two-stroke engine is straight forward that’s where the familiarly stops.

The ignition system contributes to the limitation of the power, too. It’s a capacitor discharge but unlike most others it’s not triggered by just one pulse from the crankshaft but two. The variation between the two pulses determines the timing of the spark and so makes it very difficult to modify the timing for the extra power.

In overall design, the MB5 motor shares many of the castings from the CR80R mini motor-cross engine and the H100 commuter bike. Since the CR80 pokes out 16bhp, there’s more than enough designed in strength.

The most interesting feature is the use of a balance shaft. While this might be of dubious value in the MB5, it certainly has a role to play in the higher revving versions.

The shaft is geared via a backlash pinion that also doubles as the rev counter drive, from the top of the clutch housing. The counter-balance weight therefore runs in the opposite direction to the crankshaft, and since it is 180 degrees out of phase to the bob weight on the crank, opposes it at mid stroke.

Despite that, and the use of one of the slickest five speed gearboxes ever, the performance of the MB5 is nothing like as stunning as you might expect. Flat out it will rev to over 7000rpm in top gear for a top speed of about 35mph. On hills the speed will drop to about 25mph and to keep up with open road traffic the gears have to be stirred up vigorously.

Acceleration over 100 yards from a standing start wasn’t in fact as good as some of the better single speed or two speed automatic mopeds with a time of 11.8 secs. Suzuki’s FZ50 can do it in 11.6 seconds. Where the Honda scores though is that it can get off the mark quickly and this helps at traffic lights.

Lubrication of the engine is by a separate pump, gear driven from the engine and flow controlled by throttle opening.

The pump is supplied from a small tank mounted behind the steering head. This has an awkwardly located sight glass under the frame tube on the left. The tank is filled by lifting the lid at the front of the fuel tank where the tool kit, spare fuses and a small tray reside.

The bike ran cleanly on two star fuel retaining 88mpg. With the two gallon tank, this gives a useful range of 175miles.

While that’s not as good as the 100mpg you’ll get from the lightweight mopeds, it is better than most sixteener machines.